Comparing Swift Compiler Performance on Type Inference Part I

Strings, Numbers, Arrays, Dictionaries and Constructables

Author: Lucas van Dongen

Introduction

While I was shipping a feature at work, the CI suddenly started failing because, suddenly, at some other part of the application I wasn't maintaining a given block of code exceeded the 1000ms limit set through -Xfrontend -warn-long-expression-type-checking.

A quick evaluation showed that the offending piece of code was using .init() instead of Constructable(), which made the compilation a magnitude slower. Whenwe strongly typed the initializer the issue went away and I could go ahead to get my feature shipped.

This led me to believe bare .init's should be avoided, my belief strengthened by a thread on the Swift forum that tested the compiler performance of different ways to initialize a String, where the .init variant was quite a bit slower than the typeless literal.

However when I started to do some tests myself recently I made some unexpected discoveries that were confirmed by another recent article that forced me to doubt on some earlier strong claims I made about the performance of the performance of calling .init() instead of MyConstructable():

Would I be forced to eat humblie pie this time? Was .init indeed just as fast or faster as calling the named initializer? Let's take a look at the do's and don'ts around automatic type inference regarding to automatic type inference based upon a close examination of compiler performance statistics.

TL;DR

According to my benchmarking, I have the following very strong recommendations when it comes down to compiler performance:

- When initializing a number or

String:- If it's possible, use untyped literal:

let message = "hello world" - Unless the type doesn't match the default type, use a left hand type:

let value: Decimal = 12.25

- If it's possible, use untyped literal:

- When initializing a new

DictionaryorArray:- Simply using the untyped literal is usually faster:

let dictionarySimpleUntyped1 = [ "one": 1, ... ]let mixedArrayUntyped1 = [1, nil, 1.0, Decimal(1), ...] - Unless you are nesting, in that case it helps to add the type on the left side of the assignment:

let dictionaryNestedTyped1: [String: [String: [String: Int]]] = [...]let arrayNestedTyped1: [[Any]] = [[1, nil, 1.0, Decimal(1)], ...]

- Simply using the untyped literal is usually faster:

- When initializing a Constructable (

structorclass), always use an explictly typed declaration:let value = MyConstructible() - This is especially true when there's no clear left hand type set

- The Swift compiler generally got slower over every version, except for some array literals

How Was the Test Executed?

The machine under test was a 16" 2019 2,3 GHz 8-Core Intel Core i9, but tests have been done on the M1 Max MacBook Pro that gave similar, but of course much faster results

I used the test setup as detailed here

Literals

Numbers and Strings

Literals are types that can be expressed by a literal value. The following values can be expressed using a literal, without specifying it`s type of the left side of the declaration. If you already read previous articles on how fast literals compile, you'll learn nothing new. You might want to skip to the `Array` section, where things definitely get more interesting.

- Array can use ExpressibleByArrayLiteral

- Dictionary can use ExpressibleByDictionaryLiteral

- Int can use ExpressibleByIntegerLiteral

- Double can use ExpressibleByFloatLiteral

- Bool can use ExpressibleByBooleanLiteral

- Any

nil-able value can use ExpressibleByNilLiteral - String can use ExpressibleByStringLiteral as well as some other, less used literals like for grapheme clusters

Furthermore it's also possible to declare other types through literals, like Decimal can use an ExpressibleByFloatLiteral: let decimalLiteral0: Decimal = 1.0. Note that ExpressibleByFloatLiteral actually always generates a Double value, perhaps the name was chosen when 32-bit

I've executed the following tests to see what the peformance was of various different ways of initializing these values. Most of these results were already covered by other researchers, but I'll include them anyway for sake of completeness:

| Test Name | Code Executed |

|---|---|

StringLiteral |

let a0 = "hello, world!" |

StringInitializer |

let b0 = String("hello, world!") |

StringBareInit |

let c0: String = .init("hello, world!") |

StringTypedLiteral |

let d0: String = "hello, world!" |

StringTypedBareInit |

let j0: String = String.init("hello, world!") |

IntLiteral |

let e0 = 1 |

IntInitializer |

let g0 = Int.init(1) |

IntBareInit |

let h0: Int = .init(1) |

IntTypedLiteral |

let f0: Int = 1 |

IntTypedBareInit |

let i0: Int = Int.init(1) |

DecimalLiteral |

let decimalLiteral0: Decimal = 1.0 |

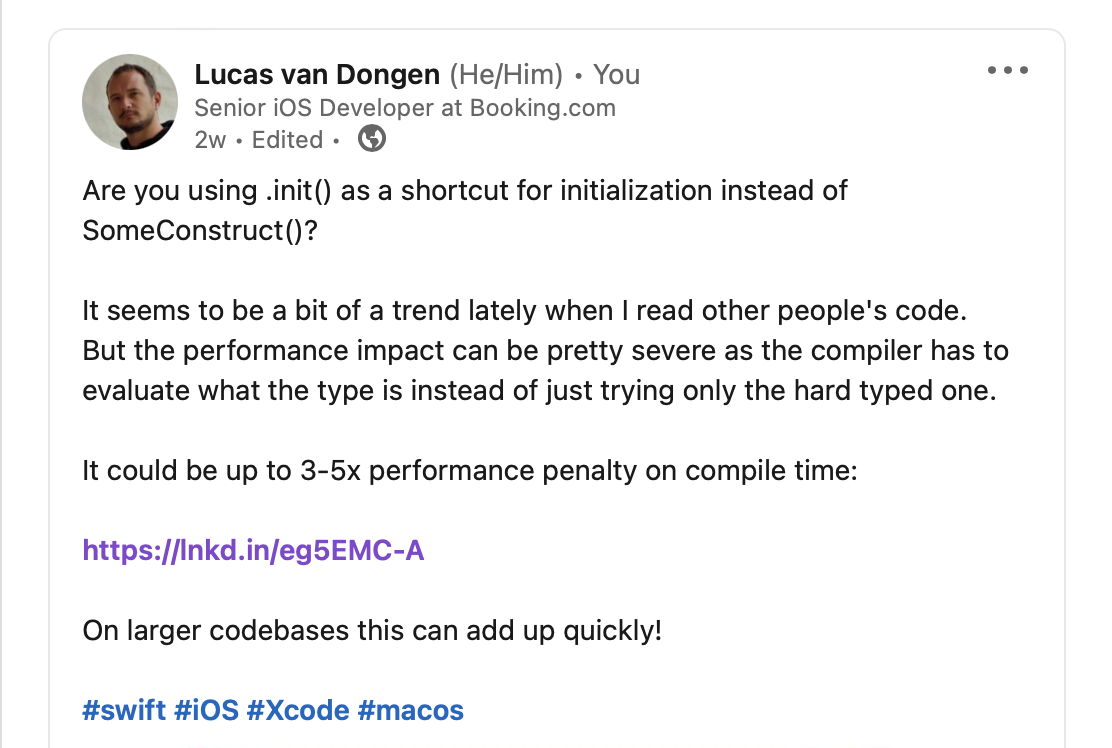

Each assignment is repeated 1000 times in the same file, then the test is repeated 10 times. Let's see the results:

Clearly, we see that the untyped literal initialization beats all other forms of initialization. Even using a literal assignment with the type specified at the left side of the declaration (StringTypedLiteral, IntTypedLiteral and DecimalLiteral) is significantly slower. The Swift compiler engineers seem to have optimized massively towards these most common scenarios.

If you need any other value than the default value of the literal, like Decimal you are forced to set the type of the left side of the assignment and experience the same kind of performance penalty as if you would specify the type for a literal Int or Double assignment.

So when you can assign a number or String literally, always omit the type unless you specifically want something different than the expected type. I assume so far everybody that reads already works like that. Let's see if we can see something interesting when we analyze the Array type.

Arrays

The big difference between the number and String literals is that an Array has an Element that confirms to a certain type. So when you create an array with a literal assignment, the type of the Element needs to be deduced by the compiler. Let's see how efficient the compiler can handle all the scenarios I could come up with.

| Test Name | Code Executed |

|---|---|

LargeArrayUntyped |

let arrayUntyped1 = ["value", ...] |

LargeArrayTyped |

let arrayTyped1: [String] = ["value", ...] |

LargeInitArray |

let arrayInit10 = Array<String>(arrayLiteral: "value", ...) |

LargeArrayRepeating |

let arrayRepeated1 = Array(repeating: "value", count: 1000) |

LargeUntypedMixedArray |

let arrayUntypedMixed1 = [1, 1.0, nil, Decimal(12), ...] |

LargeTypedMixedArray |

let arrayTypedMixed1: [Any?] = [1, 1.0, nil, Decimal(12), ...] |

LargeInitMixedArray |

let arrayInitMixed1 = Array<Any?>(arrayLiteral: 1, 1.0, nil, Decimal(12), ...) |

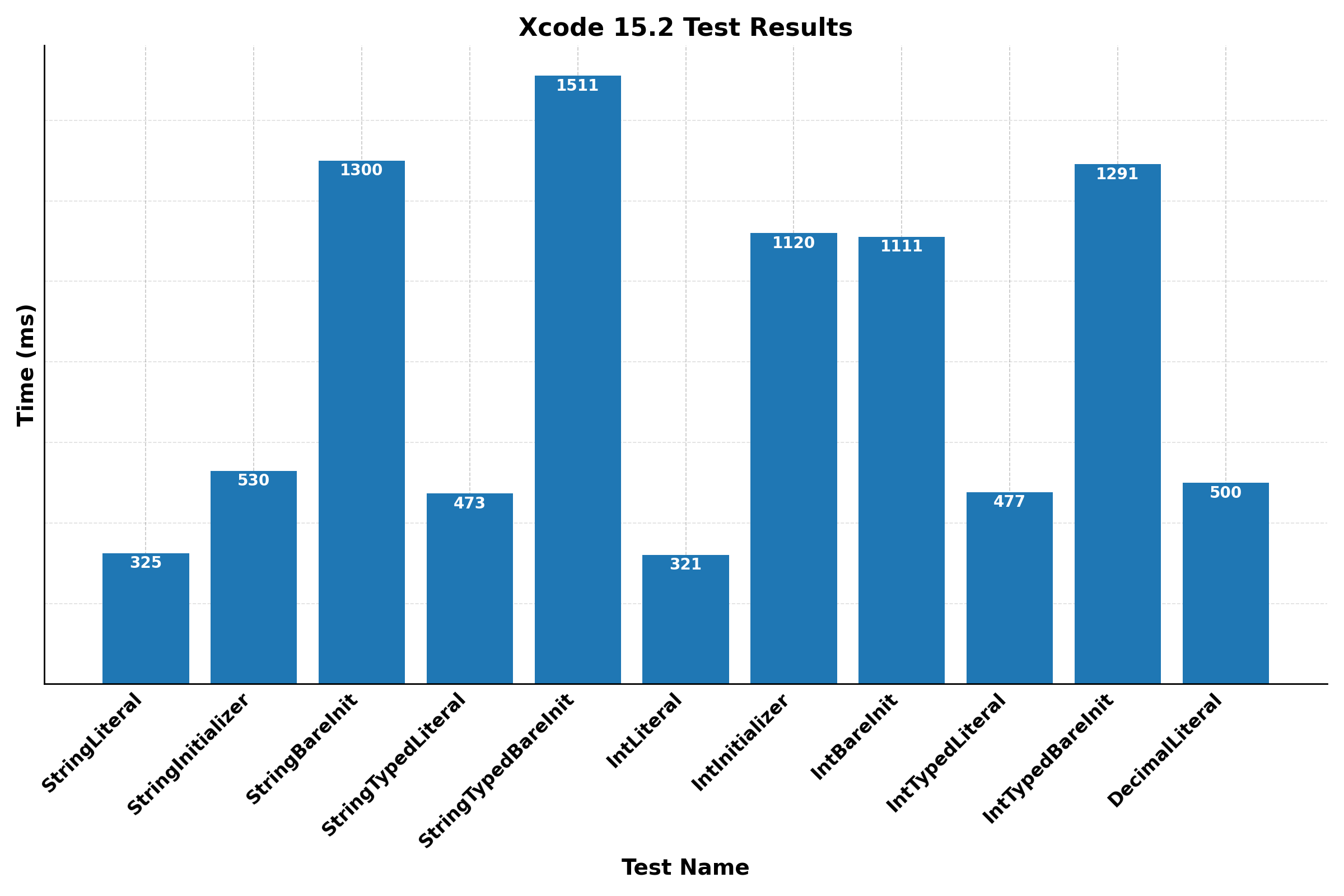

They each contain 1000 items (except for LargeArrayRepeating) and are repeated 10 times in the same file. I tried to see what happens if I would repeat the same type in an Array, as well as mixing it up a bit to see how it would handle normalizing the type down to a shared base type while parsing the declaration.

I also included Array<String>(arrayLiteral:) because the documentation claims "It is used by the compiler when you use an array literal". Another addition is Array(repeating:), which should be the fastest way to initialize and Array with exactly the same value repeated over and over.

Here we can observe some interesting effects. There is a negative impact of using a left side type declaration, even when the Array contains more than one different type. In fact, it performs worse in that case instead of just the same when the same type repeats. The Array(repeating:) performance is barely faster than using an untyped literal, despite it's declaration being 1000x larger. Impressive!

Using arrayLiteral is absolutely devastating for performance. While theoretically we should be skipping a step, it's about 4x slower. As the documentation already said: "Do not call this initializer directly. [...] Instead, create a new array by using an array literal as its value.". Lesson learned: trust the documentation.

I never used to hard type my Array literals anyway, so nothing to change here for me personally. But I did use to type my Dictionary literals in certain circumstances.

Dictionaries

The Dictionary type is the most complex type that can be expressed by a literal, as both the key and the value have a type and not every type can be used as a key. It's also often used to reflect more complex, nested data structures, for example when mocking the response of a remote API.

| Test Name | Code Executed |

|---|---|

SimpleDictionaryUntyped |

let dictionarySimpleUntyped1 = [ "one": 1, ... "twelve": 3 ] |

SimpleDictionaryTyped |

let dictionarySimpleTyped1: [String: Int] = [ "one": 1, ... "twelve": 3 ] |

NestedDictionaryUntyped |

A dictionary three levels deep (add link) |

NestedDictionaryTyped |

let dictionaryNestedTyped1: [String: [String: [String: Int]]] |

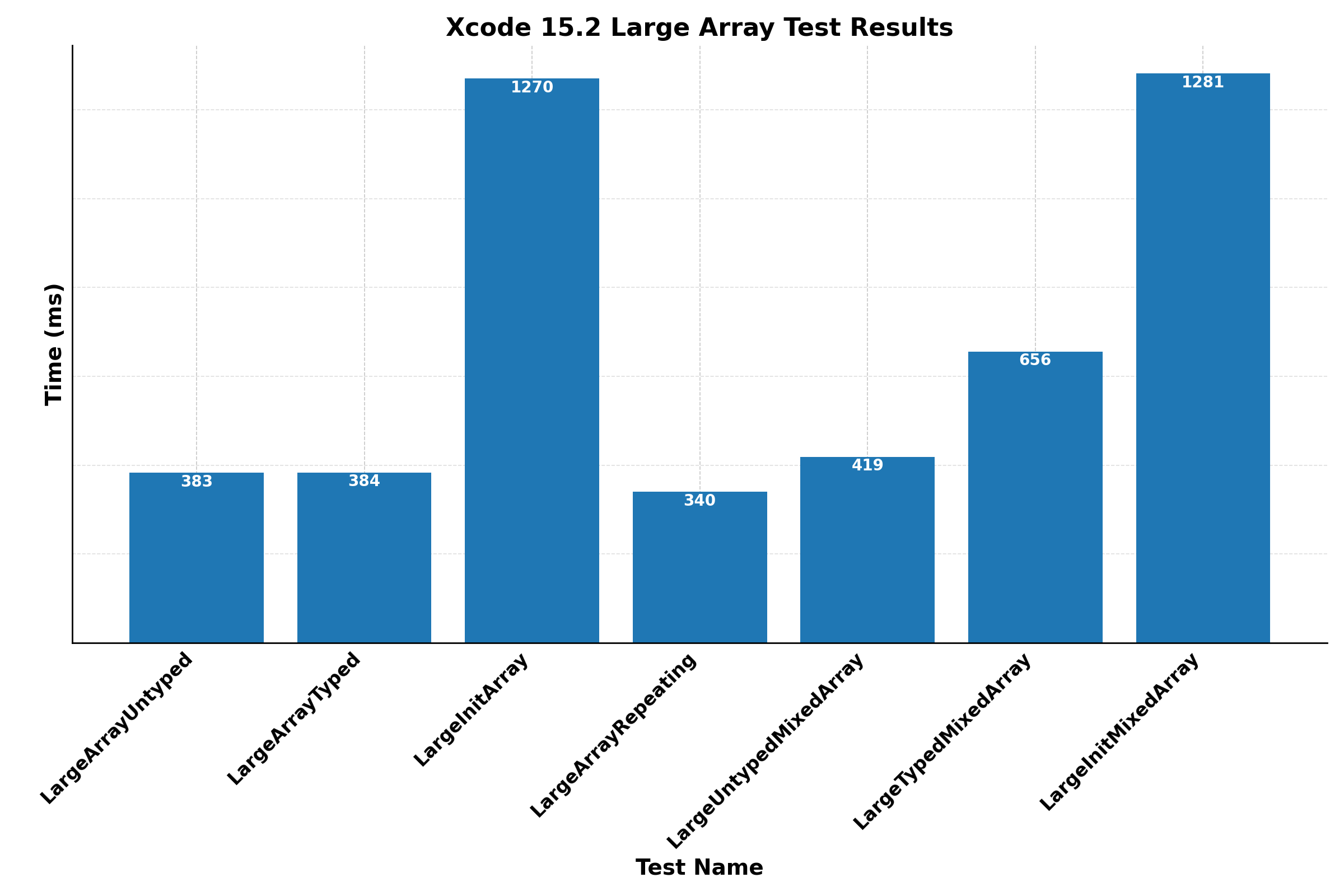

The simple Dictionary declarations were 12 items, each, repeated 682 times until roughly 11,000 lines of code were reached. The nested Dictionary was repeated just 10 times but reached roughly the same amount of lines of code.

The untyped literal performed much better in simple scenarios, but when complexity increased the typed declaration started outperforming the untyped declaration. In fact, given roughly the same amount of lines of code (with a new line for each item) there was no performance penalty compared to the simple Dictionary.

Helping out the compiler in scenarios where data is nested more than one level deep by specifying the type at the left hand definitely still pays off. In case you weren't doing this yet, this could help quite a bit.

Structs and Classes

The benchmarks I was interested most personally were Structs and Classes, as I was claiming that .init could have a large negative impact on compiler performance when creating classes.

It made sense: using .init on literals was proved to be much slower, why would a bare init (let a: MyClass = .init()) be faster when creating an instance when the left hand type needed to be compared to the .init at the right hand, while a typed initialization (let a = MyClass()) just needed to check if the initializer of MyClass was called correctly?

So I built a suite of tests that would compare different ways of initializing nested classes:

| Test Name | Code Executed |

|---|---|

| NestedBareInit | let baseBare1: Base = .init(nested1: .init(grand1: .init(), grand2: .init()), nested2: .init(grand: .init())) |

| NestedExplicitInit | let baseTyped1 = Base(nested1: Nested1(grand1: GrandChild(), grand2: GrandChild()), nested2: Nested2(grand: GrandChild())) |

| NestedExplicitInitWithLeftHand | let baseTypedLeftHand1: Base = Base(nested1: Nested1(grand1: GrandChild(), grand2: GrandChild()), nested2: Nested2(grand: GrandChild())) |

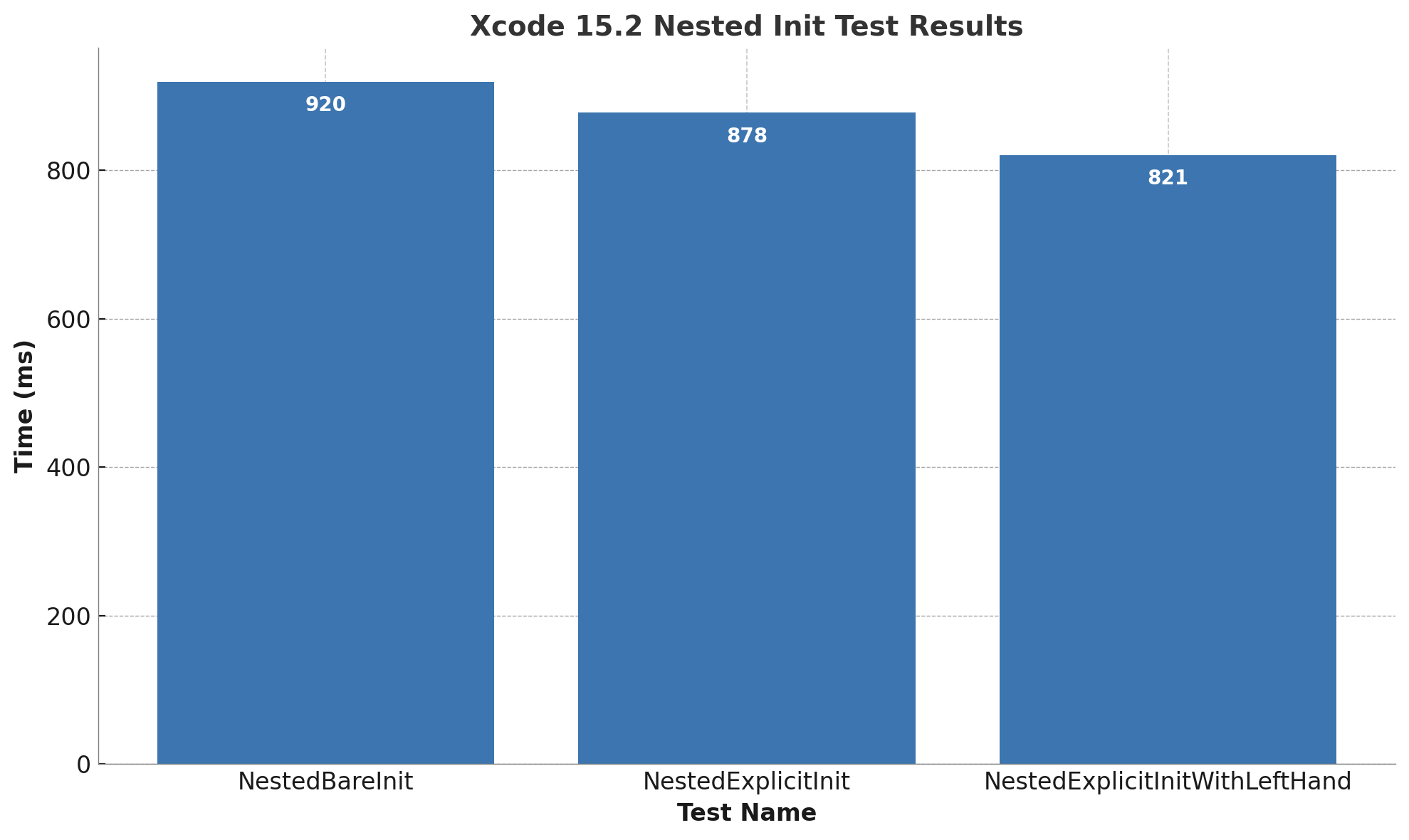

These declarations were repeated 1000x in the same file and then ran 10x. Here are the results:

As you see, being explicit is faster than using the bare init, but the differences aren't as shocking as I remember them to be. What could be the reason bare .init seemed to be peforming so poorly in my memory? Could I have been mistaken?

It was time to dig up the original offending piece of code that tripped up the type check warning.

A More Complex Context to Compile

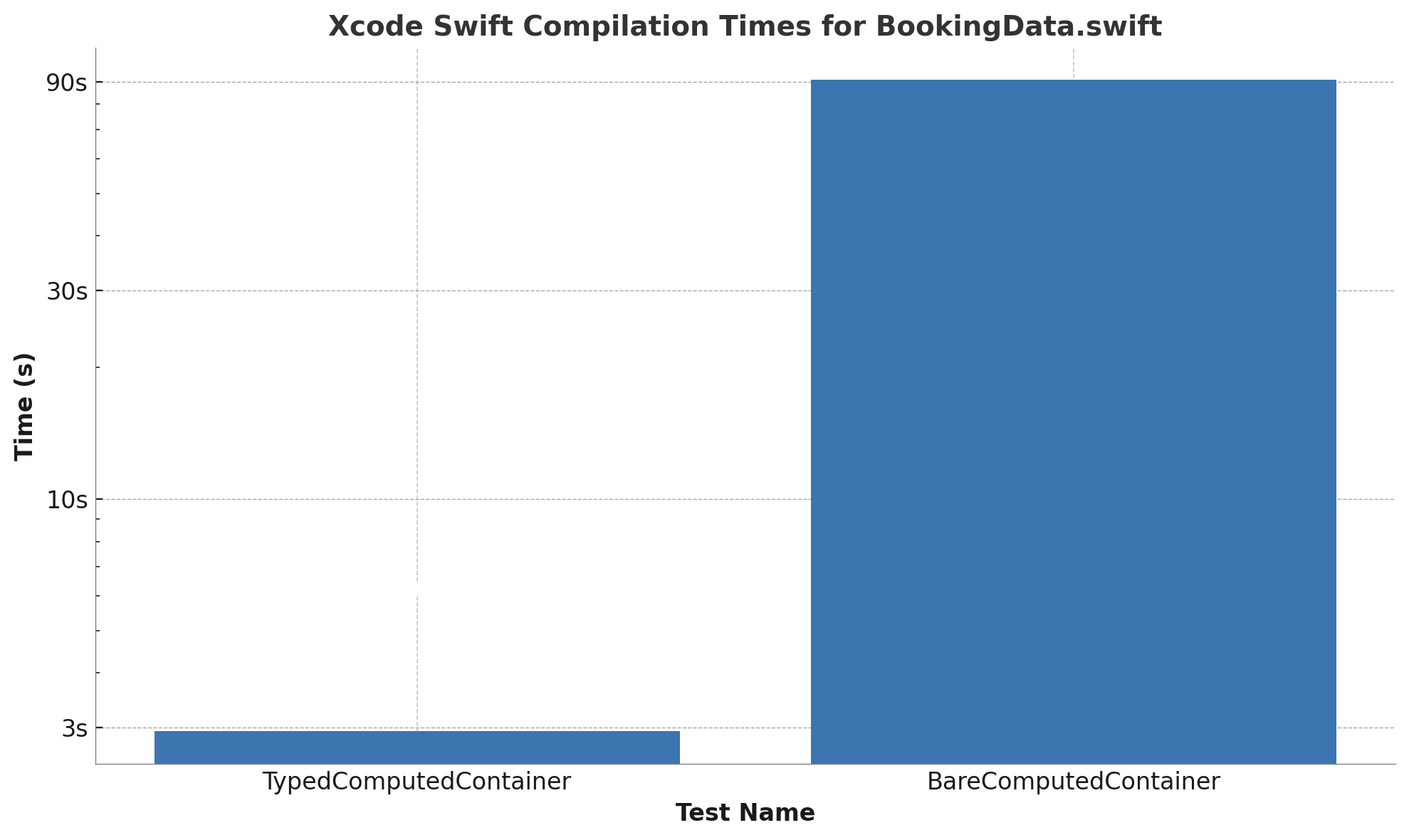

When I examined this code again, one thing struck me as different than what I was trying so far in my benchmarks: there was a more complex context. In this case, the .init happened in a computed property:

struct BareComputedContainer1 {

let id = 1

let cityName: String? = "Amsterdam"

let price: Price? = .init(currency: "EUR", public: nil, charged: 1)

let ufi: NSString = .init(string: "ufi")

let offers: [Offer] = .init()

var trackingProduct: TravelProduct {

.init(

id: id,

items: offers,

destination: .init(

type: "ufi",

name: cityName ?? "",

id: String(ufi)

),

price: .init(

currency: price?.currency ?? "",

value: price?.public ?? price?.charged ?? 0

)

)

}

}While the type of the property was clearly defined (and if it was a protocol, the .init would not compile), apparently the complexity if the evaluation became very complex for the compiler and the build time exploded. By how much?

That's what I call a smoking gun! Once the compiler has to infer the type we're initializing in this block it has too many different possibilities to try, while the typed init just needs to be evaluated if it works or doesn't work in this context.

Compiler Performance through the Versions of Xcode

When running these tests, I was able to compare the performances of the various versions of Xcode that I happened to have installed on my computer. Generally, performance worsened as we progressed in versions as the complexity of the language increased.

Only the mixed Array compilation speed got beter, especially the untyped one. Perhaps the compiler switched to a more optimized way of dealing with determining the type based upon it's contents.

Conclusions

If you're struggling with compile times, it might be worthwhile checking some of the coding styles you use when declaring variables.

When initializing a number or String, you should always use untyped literal, unless the type doesn't match the default type, use a left hand type, for example when creating a Decimal value:

let message = "hello world"

let value: Decimal = 12.25 // `Double` is the default value Dictionary or Array are generally the fastest when there's no type declaration on the left side, even with mixed types. However, when we start nesting Array and Dictionary declarations, it's recommended to add a left hand type:

* When initializing a new Dictionary or Array:

let arraySimpleUntyped1 = [ 1.0, 1, nil ]`

let arrayNestedTyped1: [[Any]] = [[ 1.0, 1, nil ], [ 1.0, 1, nil ]]

let dictionarySimpleUntyped1 = [ "one": 1 ]`

let dictionaryNestedTyped1: [String: [String: [String: Int]]] = [...]Constructables like struct or class should always use an explictly typed declaration: let value = MyConstructible(). This is slightly better in simple cases, but once more complex declarations like computed properties are used the complexity really explodes.

I think it would be really interesting to dig deeper into type inference in those scenarios, like Combine blocks where one type gets transformed into another. I remember Cartography getting so slow that I stopped using it, while I loved the syntax.

I would love to hear from you how the tests perform on your machines, especially given mine is still an Intel model and I don't have any M2 or M3 benchmarks yet. Also I would like to know if you think I should include some more scenarios to benchmark the compiler.

Stay tuned for part II of this blogpost where I test more common but complex scenarios, like map, sink, reduce, filter and other Combine related blocks, also when chained and type inference needs to be determined over multipe blocks. Also, overloaded operators can blow up the compile times when used without care. I know such issues made me abandon one of my favorite Autolayout libraries, because the compile time penalty just didn't outweigh the benefit of the beautiful syntax.

Then, I will sum up all of my discoveries in a handy Swift Compiler Performance Cheat Sheet.

Special Thanks

When I embarked on this journey I soonly discovered a few good posts by Jon Shier on the swift.org forums, where he used hyperfine and a Python script to run compiler benchmarks in a type inference compile time topic. I used this a base for my test suite. He also kindly answered some questions I had.

I could verify some of my results with an article written by Saeid Rezaeisadrabadi, getting similar results to my tests using the same hyperfine and Python method.

Paulo Fierro verified and confirmed my findings on an MacBook Pro with M1 Max / 64GB RAM running 15.1. Finally, I would like to thank Arthur Crocquevieille for unearthing the original offending code that had such a bad performance regression using .init, which I used for these benchmarks in slightly redacted form.